When implemented correctly, resisted sprint training, including high resistances, is an effective way to improve short sprint performance and acceleration mechanics. Several studies and coach reports published in the last 10 years have shown this in various populations ranging from leisure and amateur players to young athletes, track athletes, and elite professional male and female soccer players (e.g. Lahti et al. 2020; Repullo et al. 2025; Morin et al. 2022; Derakhti et al. 2021; Cahill et al. 2020).

Before programming RST, a key methodological question must be answered: how to set the loads individually, depending on the targeted stimulus within the force and velocity spectrum. As with gym work and the well-known “velocity-based training” approach, the load depends on the individual’s capacity to generate force. When targeting a specific work zone (e.g., high to maximal force), the load must be set to induce a movement within that velocity work zone. For instance, squatting within the 2-3 repetition maximum (RM) zone (high force-low velocity) requires a specific load range that differs greatly between individuals, regardless of body mass.

Clearly, using an absolute load (e.g., a 100-kg squat) or a body-mass-relative load (e.g., 150% body mass) for two individuals is an imprecise way to set the load. The same is true for resisted sprint training.

Tweet

When targeting a specific zone of the force-velocity spectrum (e.g., high propulsive horizontal force and low running velocity), setting loads for a group of athletes in absolute units (e.g., 40 kg for all) is inaccurate. Data show that setting loads in relative units (e.g., 50% body mass) is also inaccurate since two athletes might run at two different speeds with the same load in relative units, stimulating two different zones of their individual spectrum.

In a paper about RST training in young athletes, Cahill et al. showed that, on average, the load necessary to run at 50% of each participant’s top speed (50% Vdec) ranged from 71% to 107% of body mass (BM). Under the same loading conditions, Cross et al. demonstrated that the necessary load range for a cohort of track athletes and rugby players was 69 to 96% BM. Finally, my recent study of a more homogeneous group of elite U17 soccer players revealed that the necessary load range was 38 to 70 kg to achieve the same 50% Vdec individual load. The same individual mechanical stimulus (zone of the force-velocity spectrum targeted) was used, but the loads were very different. Switching loads between the lowest and highest ones will result in a programming mistake for both players. Use the same intermediate load for both players and you will make another mistake.

In conclusion, it is impossible to correctly program resisted sprinting without knowing the individual load spectrum within the training conditions (e.g., running surface, sled friction, and type of load applied).

There is no correct load setting without knowing the individual load-velocity profile

As described in a previous post and often done in gym-based training, the only way to determine the appropriate load to induce a specific mechanical condition and training stimulus is to draw and interpret the individual load-velocity (LV) profile. This is easily done in sprinting with four to five sprint trials, in which athletes reach their maximum running speed against four to five loads: no load (unresisted sprint trial) and typically light, medium, heavy, and very heavy loads. We will call this the “multiple trial” approach. This can be done with any type of resistance method (sled or exergenie pulley as in my previous post, or the 1080Sprint machine) and as described earlier, once the linear load-velocity relationship (and associated y=ax+b) equation is known, then loads can be accurately computed for any zone of the force-velocity spectrum.

However, as shown in this example, drawing the individual LV relationship requires four to five sprint trials, including one that is very heavy and one that is very fast (the two extreme points in the relationship).

Our new study addresses two key practical problems

In our recent study (preprint available here), Pedro Jiménez-Reyes and our team addressed two practical problems that we have often discussed with staff in recent years.

Problem #1: how to determine the individual load-velocity relationship without conducting a multiple-trial testing session?

No data can be generated without running a test. However, for gym-based exercises such as the squat or bench press, the individual load-velocity relationship can be determined using only two loads since a linear relationship can be defined by two experimental points instead of four to five or more. This is the basis of the “2-point method” studied and well-established by Amador García-Ramos for resistance training exercises (see a complete literature review here). Basically, if the loads differ greatly (e.g., one light and one heavy), the linear relationship and extrapolated information obtained are not different from those obtained using a more complex, time-consuming, multiple-load protocol. Therefore, there is significant interest in the “2-point method”: less time and effort for athletes, less analysis time for staff, and the same data output.

Our study aimed to test the same approach: replacing a multiple-trial method involving four to five sprints against varying resistances with a two-trial method. We chose two loads to build the entire LV relationship: a light load (25% BM) and a heavy load (75% BM). This choice was made based on practical observations and discussions/concerns reported by many staff members. It ensures that the two points used are distinct and that the maximal speed/unresisted conditions and the very heavy load condition are not used. The former allows us to draw a more robust linear LV relationship, and the latter prevents us from putting too much physical stress on the athletes during the trials with very high resistance or speed.

Contrary to one reviewer’s unconstructive conclusion that “A study based on such a design is highly impractical and should not be considered for publication, not only in xxx, but in any sports science journal,” those who have worked in high-level sports know that staff members may be reluctant to test team sports players, especially football players, for very high loads (in the gym or during sprints) and/or very high sprinting speeds.

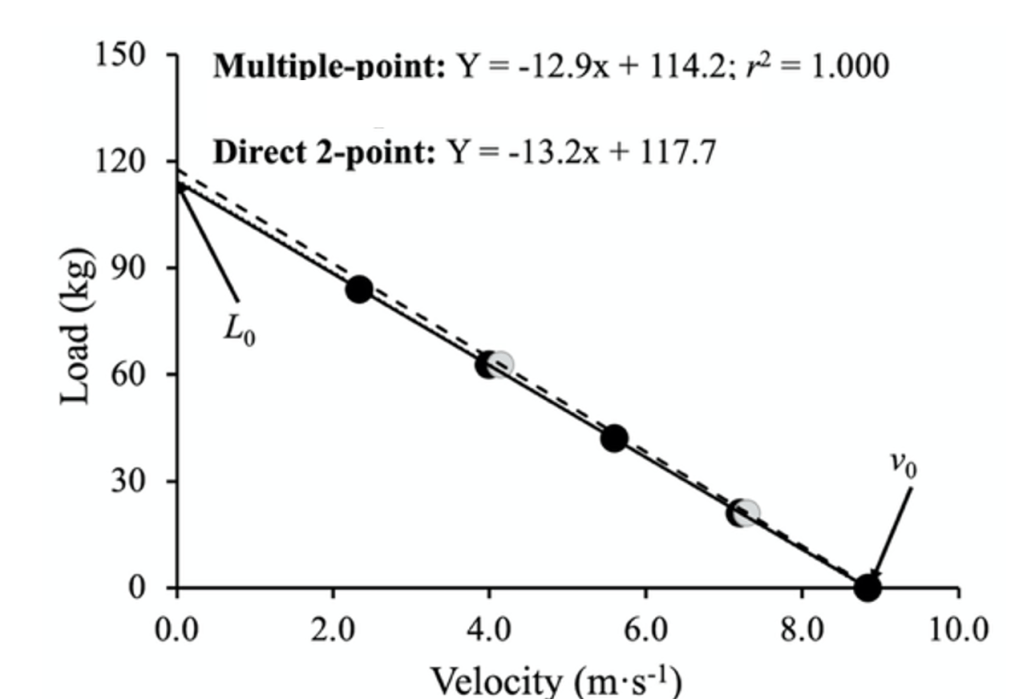

The comparison was done in a group of 23 international Rugby 7s male players, who performed two testing sessions within 3-4 days. They performed in a randomized order either the multiple-load protocol (5 sprint trials against no load, and sled loads of 25, 50, 75 and 100 %BM, black dots in Figure 2) or the 2-point protocol (2 sprint trials against the same 25 and 75 %BM sled loads only, grey dots in Figure 1). These two protocols adhere to Garcia-Ramos et al.’s recommendations for classical resistance exercises. As presented in Figure 1, for each method, the linear LV relationship was fitted (described by its slope and y-and x-intercepts) and the theoretical maximal running velocity was extrapolated as the linear relationship intercept on the velocity axis.

Statistical comparisons performed on these metrics showed that overall, the multiple-point and the 2-point data were every close (detailed results in the pre-print paper available here), as shown in Table 1:

In other words, when assessing players’ physical capacities in sprinting, the entire load-velocity relationship can be very accurately obtained by using only two loads and thus two sprint trials (25 and 75%BM), instead of a longer, more taxing complete protocol.

Tweet

Note here that the resistance is set in %BM and not in percent of velocity decrement, which is highly recommended when programming resisted sprint training (see the works of Cross et al. or Cahill et al. on why it is recommended of use %Vdec to set resisted sprinting loads instead of %BM). This is not an issue in this specific case since the objective of assessing each player’s LV profile is to obtain the linear LV relationship, to then be able to set the resistance in %Vdec when programming training. It is thus important to correctly set the training stimulus individually based on %Vdec and the LV profile, but the latter can be determined using loading conditions in %BM.

Another advantage of the two-point approach is that it enables LV assessment without requiring players to perform very demanding trials, such as the 100% BM and 0% BM (unresisted sprint), which can be physically challenging in certain contexts. The 100% BM represents very heavy load conditions that are used in some contexts (e.g., rugby) with very powerful players. In other contexts with players who are not familiar with resisted sprints, however, this load condition may require a period of familiarization. The same reviewer of this paper questioned “who tests elite athletes in resisted sprints using loads ranging from 25% to 100% BM). Can you imagine a professional forward weighing 120 kg performing resisted sprints with an additional 120-kg overload after completing maximal and resisted sprints with 25%, 50%, and 75% BM?”

Well, yes. Most elite groups (Rugby, NCAA, NFL) I’ve collaborated with in the last ten years actually do it to assess the LV profile and program accordingly, just as they do at the gym for strength exercises. It’s pretty common practice.

On a more general note, I think pulling your own body weight on a sled should be part of being physically fit, just as being able to squat, deadlift, do a farmer’s walk, and bench press your own body weight should be.

Tweet

These seem to me like good overall strength and health standards that anyone should be able to reach.

Concerning the maximal speed (unresisted) trial, which is not required when using the 2-point method this is another point where this reviewer was disconnected from reality: “There is no need to ‘estimate’ maximal sprint velocity — it must be measured directly. This is an extremely simple, safe, and regular procedure performed daily in high-performance training centers.” In my experience, many staff are reluctant to test maximal speed, especially in rugby and football. The main reason is the risk of hamstring strain associated with maximal speed testing. I think it should not be a problem, and players should be able to sprint at their top speed regularly. However, the reality in many clubs is that coaches and staff tend to avoid exposing players to top-speed testing as much as possible. In this case, it can be interesting to estimate maximal running speed from the LV relationship, just as it is interesting to estimate a squat 1RM from the LV relationship without having the athletes perform a squat 1RM. This is the second interesting application of the two-point approach.

Problem #2: How can maximal sprint speed be estimated from the load-velocity relationship if a maximal speed trial cannot be performed?

A good example of the interest in “knowing top speed without having to perform at top speed” is my work at a professional football club academy this season. A 10-week protocol was designed to improve players’ power output in sprinting, impact actions, and running mechanics to reduce the risk of hamstring injuries. A pre-protocol test was performed to determine the initial values, including the relationship between the load and velocity (LV) with four loads: 0% (top speed, unresisted trial), 25%, 50%, and 75% BM. After five weeks, we wanted to perform the same assessment to monitor player progress and potentially adjust the individual loads for the remaining five weeks of training. However, due to a major game on Sunday that would determine playoff qualification, we decided not to perform the unresisted trial. While the LV relationships could be accurately determined with the loaded sprints, the maximal running speed could not be assessed mid-program.

The solution we found was to estimate the maximum running speed for each player based on their individual LV relationship both pre- and mid-program to compare and monitor their progress. As Figures 1 and 2 and Table 1 show, this estimation is accurate. It can be helpful in scenarios where loaded sprints are possible, but maximal unloaded sprints are not. Loaded sprints are clearly less taxing for the hamstrings due to the lower running speed. I agree that this should not be the case; any player should be able to safely run at their maximum speed at any time. However, the reality in many clubs is that this seemingly simple task remains a clear problem for staff.

Similar to estimating one repetition maximum (1RM) in gym-based exercises, such as the squat, based on load-velocity (LV) profile at submaximal loads, the two-point method allows one to estimate maximal speed from submaximal speed-loaded trials.

Tweet

The advantages of the faster, more practical two-point approach in gym-based exercises (see the review by García-Ramos here) can also be observed in our proposed “Sprint two-point” approach. In my opinion, the three main advantages are the reliability of the obtained variables (LV profile, maximal load, and speed values), the faster testing process, and the less demanding process for athletes compared to multiple-load approaches.

Conclusions

Recording maximal sprint velocity against two resistive loads (approximately 25% and 75% of body mass) enables assessment of the entire load-velocity relationship of an individual and estimation of maximal unloaded running velocity. This method is similar to the multiple-load procedure, which includes an unresisted all-out sprint plus at least three resisted sprints. This two-point method could help reduce the duration and physical burden of routine testing of the load-velocity relationship without altering the quality of the output data (maximal unresisted running speed and load-velocity profile equation).

References

Jiménez-Reyes P, Garcia Ramos A, Cross M, Cuadrado Peñafiel V, Castaño-Zambudio A, Samozino P, Morin JB, 2025. The 2-point method for a simplified individualization of resisted sprint assessment and training. OSF Pre-Print: https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/8vq73_v1

Lahti J, Huuhka T, Romero V, Bezodis I, Morin JB, Häkkinen K. Changes in sprint performance and sagittal plane kinematics after heavy resisted sprint training in professional soccer players. PeerJ. 2020 ;8:e10507. doi: 10.7717/peerj.10507.

Repullo C, Castaño-Zambudio A, Del Campo-Vecino J, Jiménez-Reyes P. Resisted sprint training with combined loads improve the maximum velocity in professional female soccer. Sports Biomech. 2025 ; 1-18. doi: 10.1080/14763141.2025.2453817

Morin JB, Capelo-Ramirez F, Rodriguez-Pérez MA, Cross MR, Jimenez-Reyes P. Individual Adaptation Kinetics Following Heavy Resisted Sprint Training. J Strength Cond Res. 2022 ;36(4):1158-1161. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003546

Derakhti M, Bremec D, Kambič T, Ten Siethoff L, Psilander N. Four Weeks of Power Optimized Sprint Training Improves Sprint Performance in Adolescent Soccer Players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2021;17(9):1343-1351. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2020-0959

Cahill MJ, Oliver JL, Cronin JB, Clark K, Cross MR, Lloyd RS, Lee JE. Influence of Resisted Sled-Pull Training on the Sprint Force-Velocity Profile of Male High-School Athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2020 ;34(10):2751-2759. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003770.

Cross MR, Samozino P, Brown SR, Morin JB. A comparison between the force-velocity relationships of unloaded and sled-resisted sprinting: single vs. multiple trial methods. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2018 ;118(3):563-571. doi: 10.1007/s00421-017-3796-5.

García-Ramos A. The 2-Point Method: Theoretical Basis, Methodological Considerations, Experimental Support, and Its Application Under Field Conditions. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2023 ;18(10):1092-1100. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2023-0127.