After a tough 2024, I’m thrilled to be back to writing and sharing my thoughts on sports science and training. 2025 has been a great year. I’ve achieved some personal milestones and there have been some important new studies from my group and others that support my teaching, coaching and consulting activities. My most exciting professional milestone in 2025 was reaching 10,000 official citations for our published papers and 1 million reads for our works on my ResearchGate profile. I think these stats are a pretty good way to measure impact. Yeah, they do increase by definition over time, which makes me think about the fact that my first published paper was in 2002…

As well as looking at paper stats, the most impactful (and my favourite) thing I did in 2025 was to travel around the world (literally… I flew around 30,000 km and rode 20,000 km by train) and share knowledge and practical experience with over a thousand coaches, physios and sports science students. I could visit five new countries and discover cultures, which is definitely the best part of the job. I’ve already got most of 2026 sorted, with the U.S., Mexico, Prague and some great conferences and staff meetings planned around one of my favourite sports: basketball. I’ve got to say, going to a playoff game at the Madison Square Garden was probably the best travel experience I had in 2025.

Now, let’s get back to the science and the 2025 projects we can’t afford to miss. This year, we’re focusing on sprint mechanics and hamstring injuries, strengthening your feet and ankles, using resistance to improve your sprinting performance, and how position tracking can be used in team sports and athletics.

Sprint mechanics and hamstring injury risk

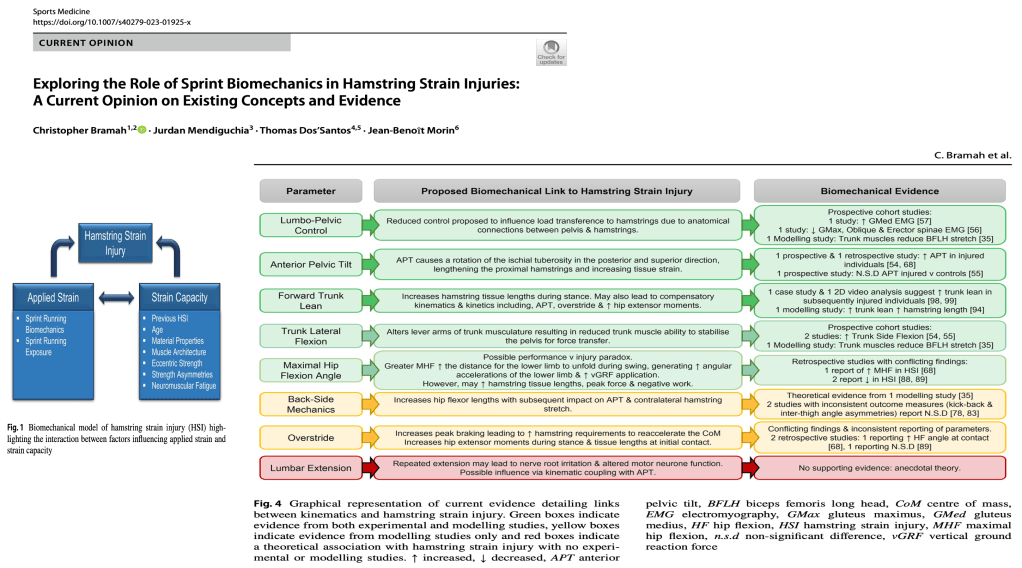

2025 was a game-changer for research into how sprint mechanics impact hamstring muscle strain and, as a result, the risk of injury. For years, there was a big argument going on about whether there was any proof of a relationship, with some people saying “there’s no evidence, so there’s no relationship” and others saying “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence”. People like Chris Bramah, Jurdan Mendiguchia and myself were on the “we need to study things” side of this debate. Back in 2023, we published an opinion piece for Sports Medicine that looked at the links between sprint biomechanics and hamstring strain, and the existing evidence or justifications from functional anatomy.

We discussed these points in detail with Chris in two podcasts:

Listen to the Podcast here: https://www.just-fly-sports.com/podcast-387/

And this was the topic of a conference I’ve made at Sportsmith online.

The main thing to remember is that when you’re running fast or sprinting, you’re putting a lot of strain on your hamstrings. This is mostly because of (i) leaning forward and rotating your trunk, (ii) tilting your pelvis forward during the whole step cycle, especially during the swing and late swing phases, (iii) stepping forward with your leg too far when it hits the ground in front of your centre of mass, and (iv) your trailing leg moving backwards at the same time, which creates a big gap between your thighs or knees. So, how are these features of the running pattern related to hamstring length and strain?

- 1. The way you lean and rotate your trunk affects how much your posterior thigh muscles are stretched, and this is because of the connections involving fascia and the pelvis. Also, remember that the muscles in your trunk and lower limbs are attached to the pelvis, so they can affect each other’s tension. Also, the trunk segment is long and heavy, so even slight trunk inclines can create significant lever arms and torques at the proximal insertions.

- 2. The hamstrings attach to the pelvic bone (ischiatic tuberosity) at the pelvis, so if you tilt your pelvis forward, it stretches the hamstrings. In a really interesting study on cadavers, Jurdan Mendiguchia and his team showed that pelvic tilt was the main thing causing hamstring stretch, more so than hip or knee rotation. Check out the great video summary here.

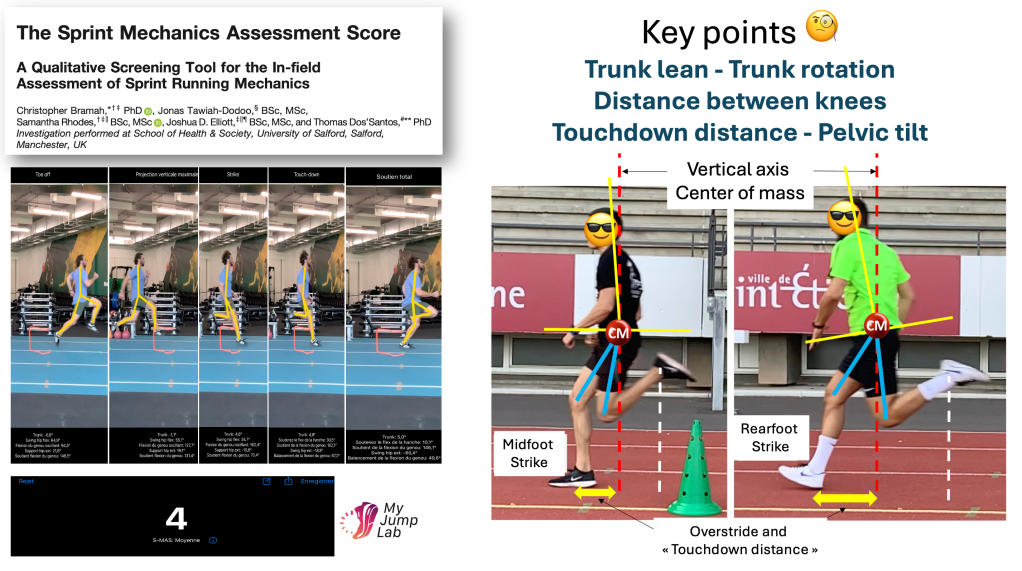

- 3. When you “overstride”, it can make your hip flexion really pronounced (which basically stretches your hamstrings), and it’s often linked to a lot of knee extension too (same result there). Sometimes, it can even lead to a rearfoot strike (check out the picture below). All these running mechanics add lengthening and mechanical strain to the hamstrings.

- 4. At the same time, if the leg that’s behind (the trailing limb) is late and there’s a big gap between the knees, the trailing thigh is pulling the pelvis into an anterior tilt, which adds to more hamstring strain.

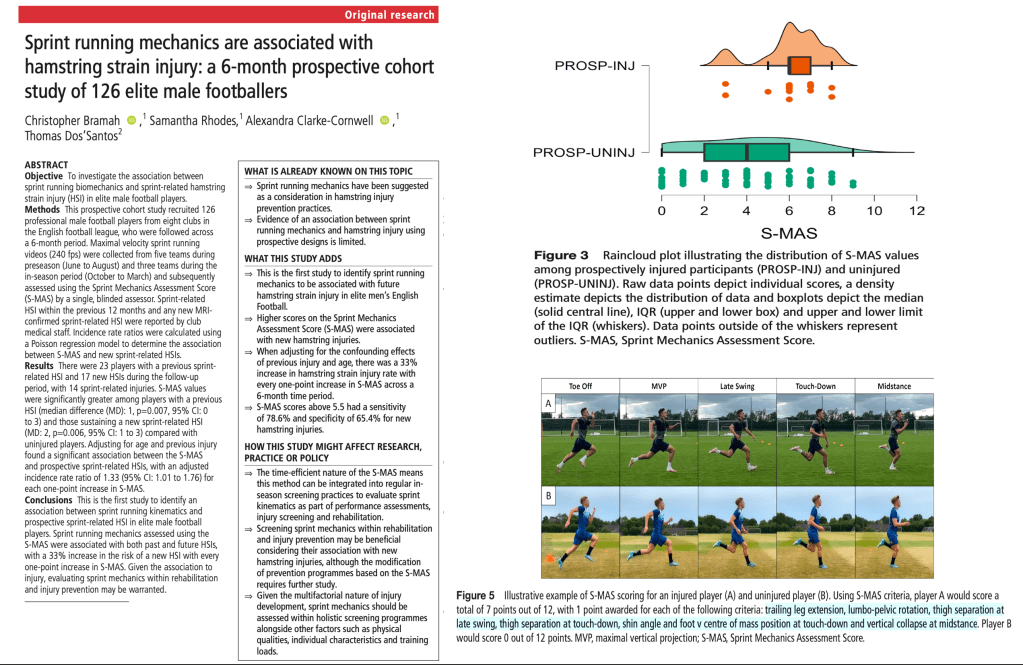

Chris Bramah has come up with a clinical score, the “S-MAS score”, to help cut through all the variables and time-consuming analyses that come with running biomechanics analysis. It gives you a quick summary of the most important features of the maximal speed sprint pattern linked to hamstring strain. On a scale from 0 to 12, the higher the score, the higher the theoretical strain. This score is based on 12 clinical-qualitative questions. They come from a slow-motion analysis of a sprint stride at top speed. It’s also part of the MyJumpLab package, which gives you the S-MAS score and the main segment angles.

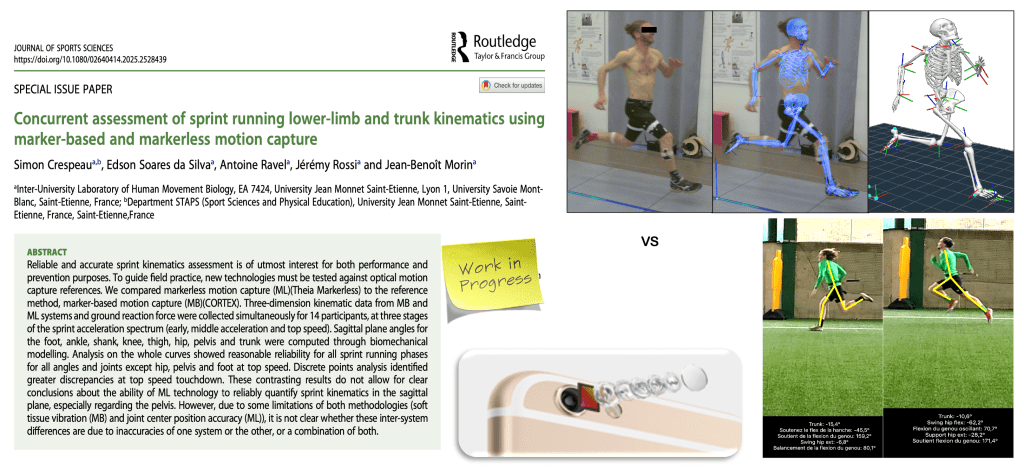

By 2025, we’d started working on how reliable these sprint mechanics measurements are. We’re using 3D motion capture systems in the lab as a reference, instead of markerless technology and simple 2D measurements, like the ones you can get from the MyJumpLab app. For example, we used this approach to describe the movements of high-level American football players (NCAA Division I) for the first time in a 2025 paper by Cameron Josse, a PhD student I’m supervising in collaboration with Ken Clark, who joined the Detroit Lions’ NFL staff in 2025. I’m also supervising another PhD student, Simon Crespeau, PT, who is currently working on these comparisons and his first 2025 paper was published in the Journal of Sports Sciences. This compared 2D markerless measurements (Theia system) to reference 3D motion capture. More to come in 2026.

The most interesting paper of 2025 was the prospective cohort study led by Chris Bramah, which looked at professional English soccer. It showed that there’s a big link between “risky” sprint mechanics (a high S-MAS score) and both past and future hamstring injuries. So, as well as the clear links between sprint running mechanics (especially the positions and angles of the trunk, pelvis and lower limbs), there’s now proof that it’s linked to a higher risk of future hamstring injuries. This confirms pilot results from the 2017 study by Schuermans et al. Obviously, injuries come from many different causes, so we need to think about other factors like how much force is used during a sprint, how much force is produced when accelerating, how strong the hamstrings are on their own, mobility, control of the trunk, lower back and pelvis, and overall health habits. But when it comes to managing hamstring injuries, sprint kinematics can’t be ignored. This paper was published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, one of the top journals in the field. We had already published an editorial in 2022 suggesting that the main injury mechanism (sprinting) should be at the centre of the problem.

The key point here is that three studies led by Jurdan Mendiguchia have clearly shown that a specific gait retraining programme can change running speed patterns to reduce hamstring strain. Astrella and their team published a paper in 2025 that showed clear changes in top speed running mechanics, this time in high-level soccer players, and saw changes like a more upright trunk, reduced front pelvic tilt, and overstriding. They also saw changes in how the trunk, pelvis, and thigh worked together during specific soccer tasks like ball driving and sprint+cross plays. You can find the detailed programme used in these three studies here. I’ve been using parts of this programme in my personal coaching practice with U17 soccer players at a professional club academy this season, and I’ve tried out some new exercises based on the same principles: lumbopelvic control challenge, unipodal stance, very short actions. You can find most of these exercises on my Instagram profile and in the video below (in French). I also teach them and explain the thinking behind each exercise during the workshops.

2025 take-home message: The answer is yes. Top speed running mechanics are related to hamstring strain and injury risk. But they can be modified to reduce strain. All you need is a specific programme comprising three 45-minute sessions per week for at least six weeks.

Foot-ankle strength

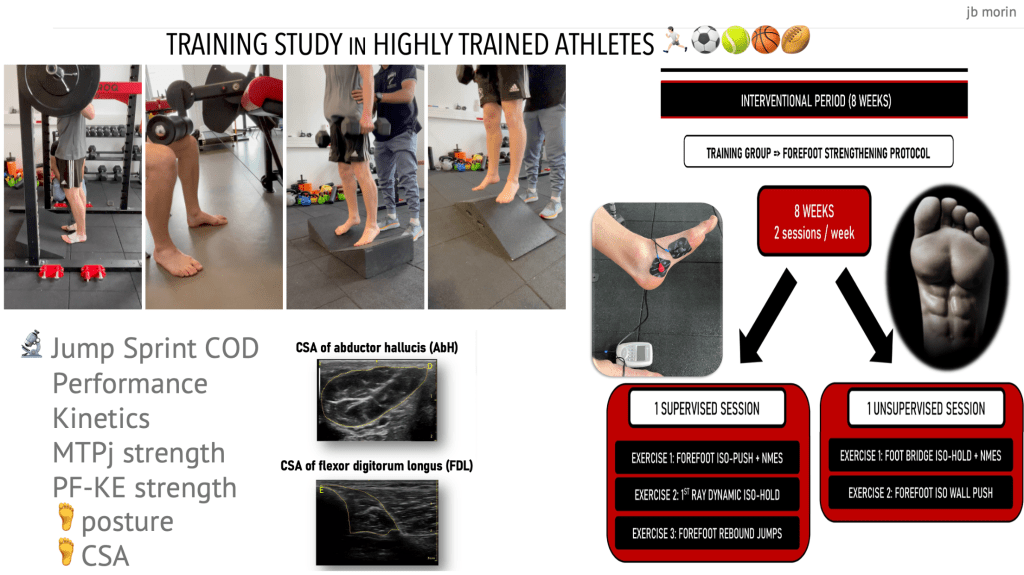

This topic has been a focus of our research since 2020 and a key to my training practice for years. After showing in a 2024 study that foot metatarso-phalangeal (MTP) torque capability was correlated to key mechanical underpinnings of jump, change of direction and top speed performance (e.g. ground impulse at top speed or during a broad jump or force orientation during a change of direction), Romain Tourillon passed his PhD under my supervision with a great training study published in 2025.

In this intervention study, we trained high-level athletes (basketball, athletics, tennis, and various high-intensity sports) for 8 weeks using exercises specifically designed to strengthen the MTP flexor muscles. The originality of our protocol was that contrary to previous studies, we followed strength training principles with significant overload and progressivity. In our case, overload was provided using additional load (for example loaded bar or dumbells in forward leaning or jumping on incline surfaces) or electrical stimulation applied directly to the foot muscles with a compex stimulation system. An indication that this program was closer to classic lower body strength programs rather than classic “foot strength” programs was that some participants (although highly trained and used to plyometric tasks and high-intensity sprints, jumps and changes of direction) reported pain and DOMS within the foot muscles after the first sessions…a good sign of stimulus and future effectiveness of the program.

The main results showed increase in MTP flexion strength in the intervention group, foot muscle volume and better impulse or force orientation during jumping and cutting tasks, along with better vertical impulse during top speed sprinting. These positive changes were still observed after 4 weeks after the end of the training sessions, suggesting long-lasting effects. Interestingly, our measures of knee extension and plantar flexion strength showed no changes after the training program, which shows that the (i) our program was selective and really focused on foot muscles strength and (ii) all the changes in jump-sprint-COD performance and mechanics observed were solely associated with the observed “foot strength” gains.

The study is open access and available here, and the paper includes links to the entire program description, exercises videos and tutorials. You can also find plenty of foot-ankle and lumbopelvic control exercises on my Youtube Channel. Finally, as discussed in a 2024 review of literature on the topic, significant strength gains can also be obtained by simply wearing minimalist shoes in your everyday life. I notice more and more athletes (e.g. LeBron James, Gabby Williams) posting strength training videos in which they train barefoot or wearing socks or minimalist shoes. It makes total sense to me: same strength session for the other muscles, more efficient strength session for the foot muscles. Win-win.

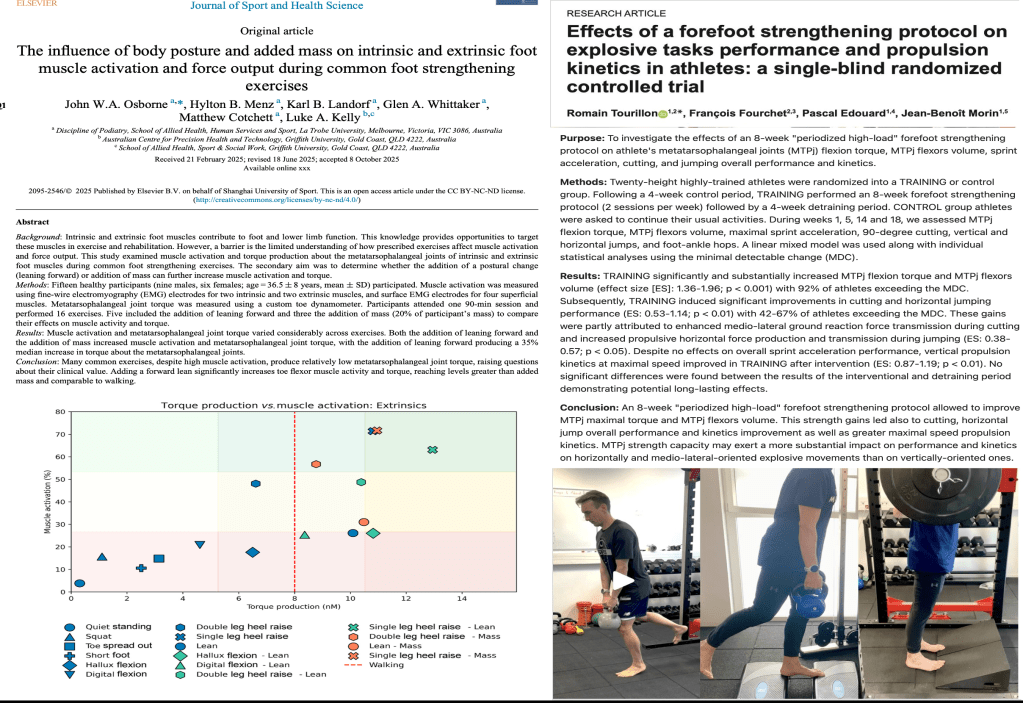

As shown in the figure above, another option to increase foot muscles activity/tension and thus likely strength training gains is to simply perform strength tasks, when possible, adding the “lean forward” instruction and using an additional mass. This is exactly how most of the exercises we used in our protocol were designed. Try it, just stand quiet and then lean your body overall forward until you feel your heels raising, not more. The tension in your foot muscles is clearly increasing, just from the increase in torque around the MTP joint. Add a barbell on your shoulders and it’s even better. This is what was shown in a recent study from Australia, based on muscles electromyography and biomechanics assessments.

Finally, check the red line in the Australian study: the torque production is pretty high compared to standard foot strength exercises right? This line shows the walking reference. So yes, simply walking (even better, barefoot walking or walking in minimalist shoes) is already a significant stimulus for foot muscles strength.

2025 take-home message : yes, foot strengthening is possible even in highly-trained athletes, and yes, it will induce positive mechanical and performance changes in jumping, sprinting and cutting tasks, with no parallel changes in knee extension or ankle plantarflexion strength. Increasing foot strength requires specific exercises and sessions performed barefoot, with significant overload. It can also be done with high volumes of walking in minimalist shoes.

Resisted sprinting

So, on the topic of building strength in your feet and ankles, I’m pretty sure (though we need more scientific proof) that sprinting against resistance is a great way to boost the strength of the muscles in your ankles and even the foot MTP joints. Why? All you need to do is to keep an eye on how your feet and ankles behave when you’re sprinting with a lot of resistance and feel the tension in your foot and calf muscles and tendons, both during and in the hours and days after a session like this. It’s pretty likely that your first session with a high load (which slows you down by 50% of your maximum running speed or more) will give you DOMS in your calf muscles and tendons, and maybe even in your foot. This is practical proof that the stimulus was unusually strong for these structures, so it’s great for strengthening them, as long as you dose it right and gradually. I’ll always remember this elite young tennis player we tested at the French Federation training centre. He’d never done high-resistance sprints before, so we had him do a single sprint against 25, 50 and 75% of his body mass (3 trials, he was 18 and playing world-class level for his age group). Not more. The next day, he came to the gym with compression sleeves on his calves, saying he had tension and soreness.

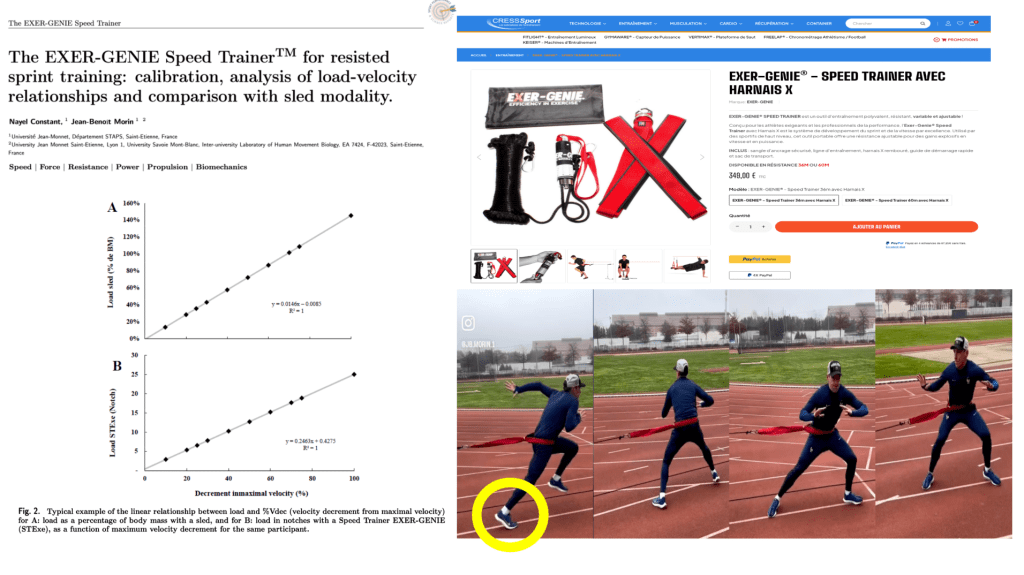

Since 2025, I’ve been using the Exergenie pulley device more and more in teaching and training. I’d definitely recommend it as a cheap and easy-to-use alternative to sleds. If you can measure running speed during reps, you can easily work out the load-velocity with this device. You can then compare it to your usual resistance modality (e.g. sled) as I explained in my previous blog post and in our 2025 paper here.

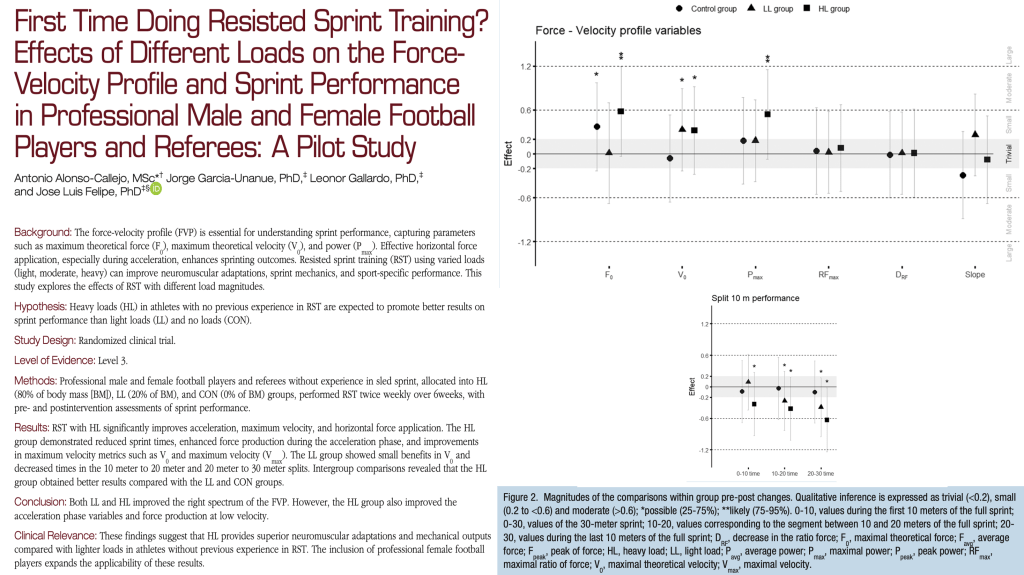

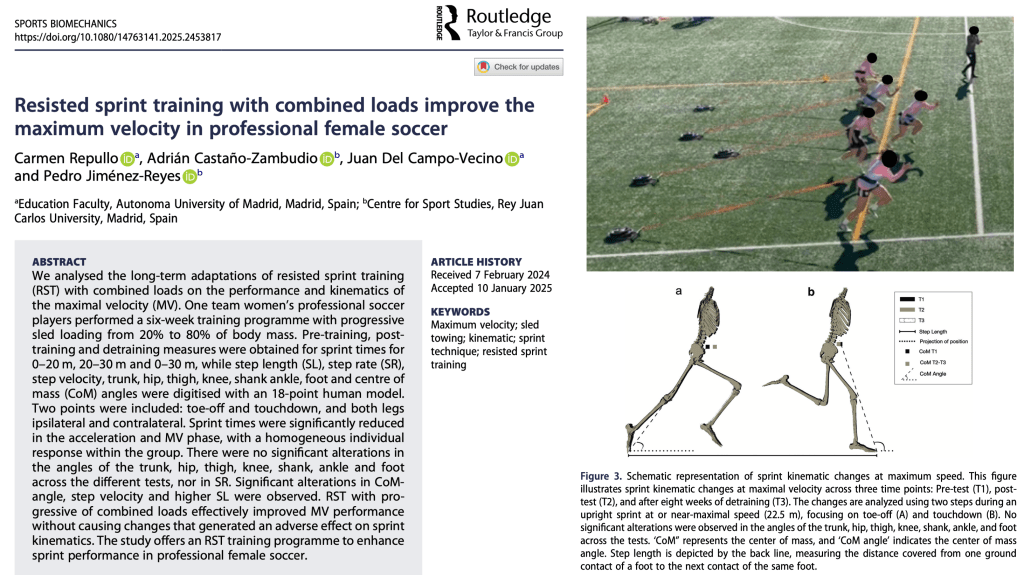

In line with our previous training studies on this topic, we published in 2025 a paper on resisted sprint training that compared the same overall volume of training with individual loads, which reduced the speed by 50% (50%Vdec). This was programmed with short sprints and a high number of reps (8 times 12.5 m per session) versus longer sprints and a lower number of reps (5 times 20 m). Basically, the big picture was that both methods resulted in a notable increase in sprint acceleration power output, with no obvious differences between them. So, it looks like the same overall working volume can be managed in different ways, with no obvious impact on the training outcomes. The other result is that, like in a bunch of previous studies in my group or by other people, heavy resistance sprint training (50% Vdec or less) leads to clear gains in sprint acceleration power, which is a key physical part of loads of sports. We’ve seen some really positive effects from these training loads, since our 2017 pilot study with male soccer players, young athletes, track athletes, young soccer players, and, most recently, high-level women’s soccer players (Repullo et al.). A 2025 study by Alonso-Callejo et al. has shown that even beginners can benefit from heavy RST (80% body mass). I don’t think it’s a discussion anymore. If you want to improve your early acceleration, force and power output and performance, then heavy resistance sprint training is the way to go.

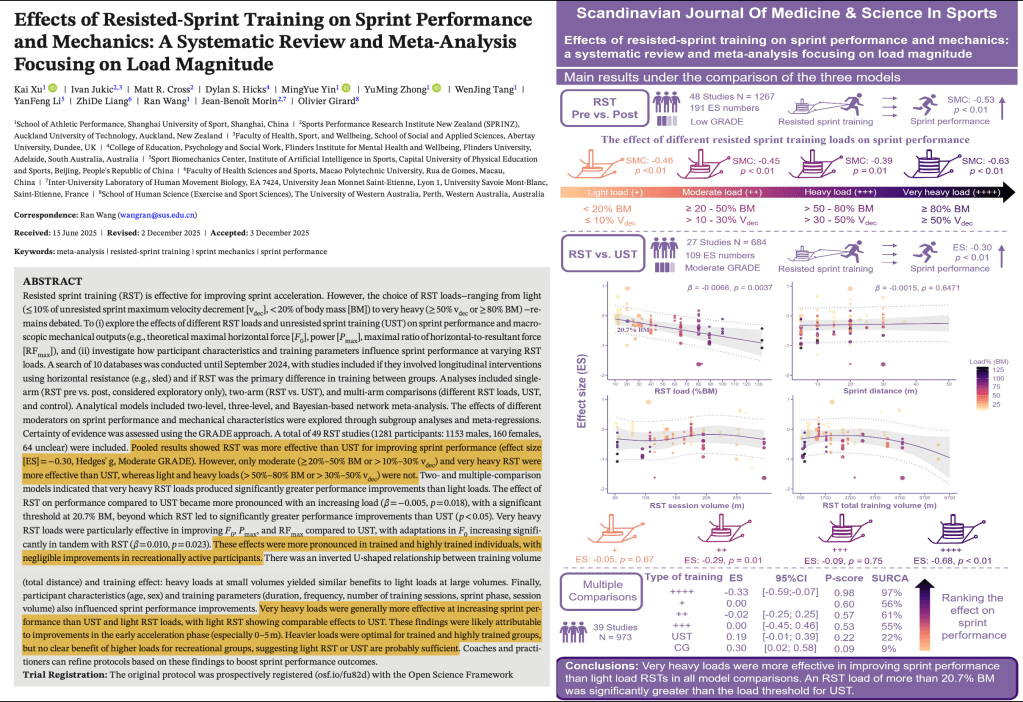

To confirm this, we did a detailed systematic review of the research, which was published in 2025. In the review, we looked at the results of training studies and used load as a factor. It doesn’t make sense to compare “Resisted Sprint Training” to “Unresisted Sprint Training” as some studies do, putting all of these under the same “RST” banner, from super light to super heavy loads. It’d be a bit like talking about gym “resistance training” without mentioning the different weights you use! It might sound unbelievable, but this is what most studies on RST have shown so far. This new meta-analysis is really interesting, especially the bit about squatting with heavy loads being better for increasing 1RM than squat jumps.

To put it simply, you won’t get stronger at squatting by doing air squats or light load squats. And the same goes for the sprint acceleration strength output.

This meta-analysis confirms that the effects of RST depend on the load, which is why it’s important to consider the individual load-velocity relationship to correctly set training loads, as I explained in my previous blog post. I hope RST studies will only propose individualised, load-velocity based programmes, instead of non-individualised loads. When it comes to training, our meta-analysis shows that RST should be designed with loads set as a function of the targeted gains (early acceleration, maximal power output, maximal speed, etc.) to follow the load specificity described in our study. When it comes to early acceleration metrics, heavy resistance is the way to go.

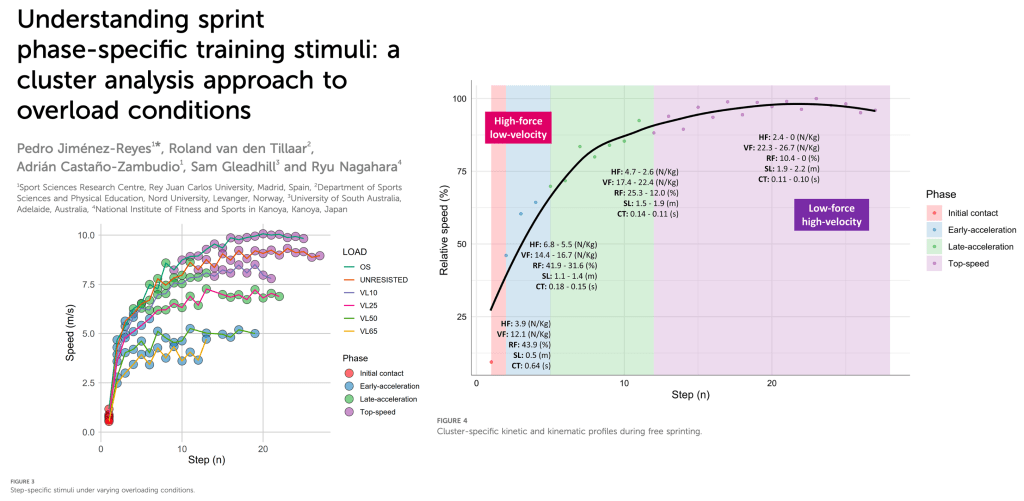

This result matches up with the “dynamic similarity” talked about in a 2024 paper by Pedro Jimenez-Reyes and his team. In this really good study, they used a fully instrumented track with force plates and showed that for running speeds that are the same, resisted and unresisted sprinting have very similar running mechanics. So, if you use RST loads to do your running at specifically selected speeds (depending on the sprint phase you want to develop), you’ll be able to run under load and follow the same mechanical pattern. And then of course you’ll need to integrate this into a more macroscopic training plan to improve overall sprint performance.

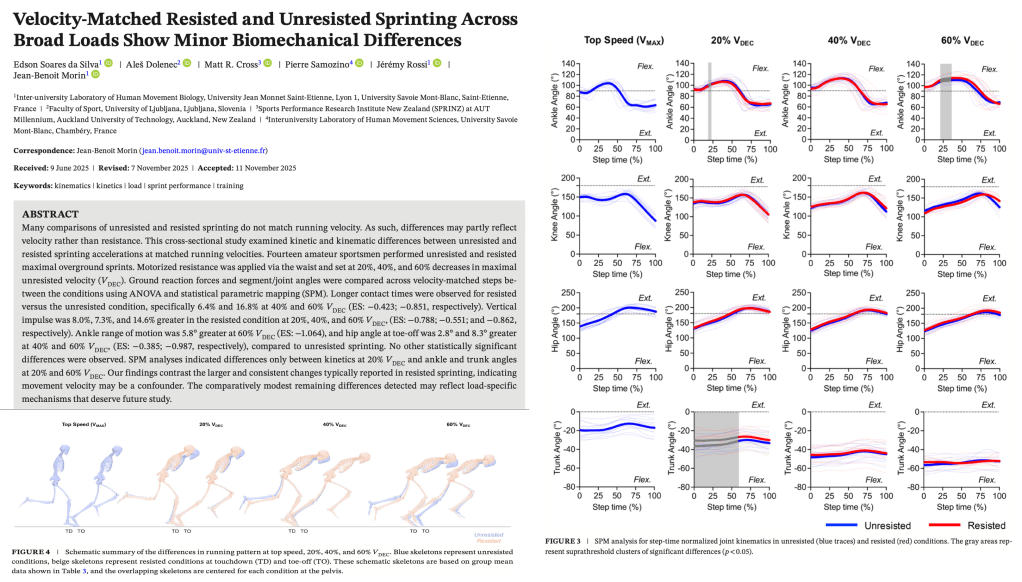

This similarity was confirmed in our 2025 study led by Edson Soares da Silva. We compared sprinting with and without resistance at different speeds to see how running speed affects sprint mechanics. This allowed us to check the “true” direct effect of resistance on sprint mechanics, separate from running speed (which has a big influence on running mechanics).

A minority of authors say that RST and especially heavy RST shouldn’t be used because of big changes in running mechanics. The problem is that the changes in running mechanics they report were coming with clear acute changes in running speed when running against loads (I had fun reading a study where the main result was that running speed was decreasing as resistance loads were increasing…do we really need a study to show that?). Naturally, mechanics will change if we compare unresisted sprinting maximal speed to resisted sprinting maximal speed, since these two speeds are clearly different. In our study, we compared these two types of sprinting by matching the conditions (resisted versus unresisted) and then comparing the steps taken at the same running speed. The main thing we found out was that, out of all the different kinetic (ground reaction force) and kinematic (segment angles and positions) variables we looked at, only a few showed any significant differences. So, when you compare them at the same speed, unresisted and resisted sprinting are pretty much the same when it comes to how they work. This is totally in line with the studies of Jimenez-Reyes et al. in 2024 and Sugisaki et al. in 2023. Some studies have said that the change in running mechanics caused by resistance is down to the resistance itself, but this isn’t the case. It’s more to do with the different running speed that comes with it.

This important result made a lot of coaches think again about how RST is seen: It’s the only way to overload the sprint pattern in a specific way, which makes the muscles and tendons used for sprinting stronger. This in turns improves how quickly you can sprint. Also, the amount of resistance you use should match your training goals. As well as these results in the literature, I’ve got loads of examples of how coaches and staff have used RST and heavy RST in high-power sprint sports. I’m now sure that, if it’s done right, it’s a great training method.

So, about that question of how training changes your sprint pattern (kinematics), a study from 2025 by Repullo and her team confirmed what we found in 2020: that athletes (here high-level women’s football players) didn’t show any major changes in their running mechanics after a pretty tough RST programme. As lots of coaches have been asking about this, it’s worth remembering that the only two studies done so far on maximal speed running mechanics after a heavy RST programme have shown the same thing: no change. We chat about this and other related topics in the Football Fitness Federation Podcast here:

2025 take-home message: Yes, You can improve your sprint acceleration, force, power and performance by doing resisted sprint training. The load you use is important, and you should set it in line with the effects you want to achieve. For example, if you target early sprint acceleration mechanics and performance improvements, heavy weights should be your main focus. No, resisted sprints don’t cause specific changes to running patterns, other than the acute ones that come with changing running speed. And no, a training programme with resisted sprints doesn’t alter the running pattern in football players.

Team sports Acceleration-Speed profile and new satellite tracking applications

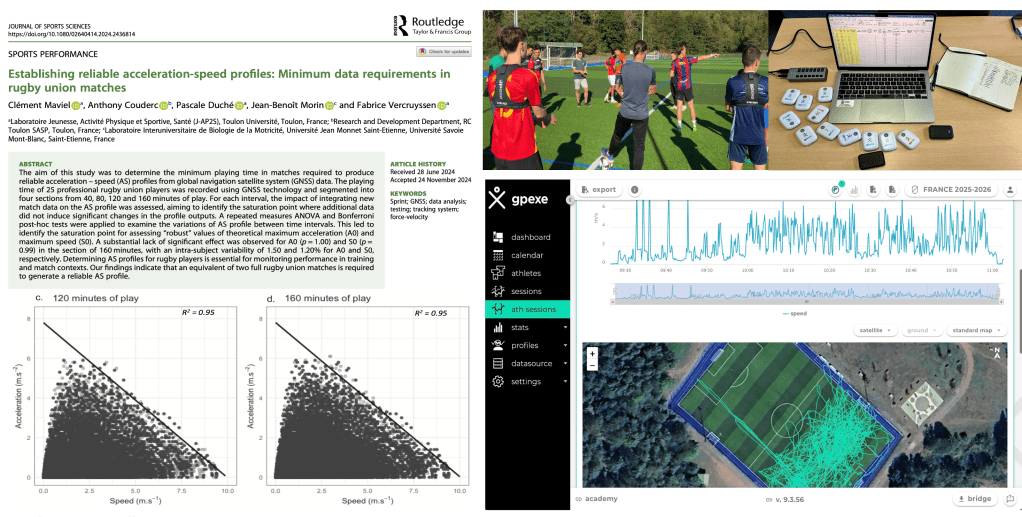

Since our proof-of-concept paper in 2019, the in-situ profile of acceleration and speed outputs in field-based team sports (initially soccer) has developed in the literature in soccer (e.g. Patrick Cormier or Pauline Clavel’s works) but also in rugby (e.g. the very interesting methodological paper with associated open source code by Miguens et al.). In 2025, Clément Maviel published this paper on how to build and interpret reliable AS profiles in elite rugby. He was working on a PhD project at RC Toulon rugby at the time. If you’re not familiar with this concept, you can read a previous blog post or listen to the podcast we did with Martin Buchheit in 2024.

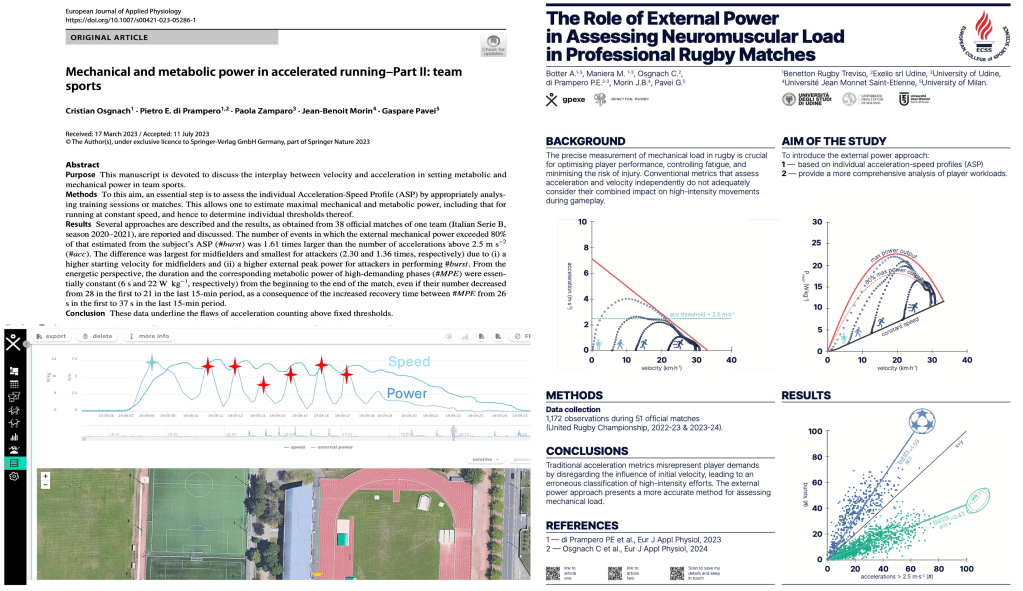

Another important idea to describe the physical demands of high-intensity sports like sprinting and team sports is the “bursts” of external power. So, as this 2023 paper by Osgnach et al. says, if we only think about running speed or acceleration (the change in running speed/velocity over time), we won’t really understand the players’ mechanical power output. Here, we’re talking about external mechanical power related to acceleration, which basically corresponds to the change in kinetic energy over time. As the paper says, if you simplify “external mechanical power” using Newton’s laws of motion, you can get a practical result by multiplying acceleration by running speed at a given time. Basically, when you’re running in a certain direction on the football or rugby field, how fast you go is directly related to how much force you push out and to your body mass (that’s Newton’s basic law of motion). Basically, the acceleration in m/s² is the same as the net propulsive force in the same direction, just expressed in N/kg. But, as you know, a given amount of acceleration (say a low value of 1 or 2 m/s2) doesn’t require the same effort when it’s produced at a low or a high running speed. As we all know, the faster we run, the less we can accelerate. This is because acceleration capacity is inversely proportional to running speed. You can read all about it in a fundamental paper by Sondereger et al. from 2016.

But if you only look at acceleration thresholds (eg 2.5 m/s2) to describe and measure “high-intensity events” in team sports, you might miss things by not including efforts below the acceleration threshold. These are done at speeds where the acceleration-speed “mix” actually represents a significant amount of mechanical power. So, if you speed up to 3 m/s² during a short sprint with a still start while running at 1 m/s, it’ll count as one “acceleration event”. But if you speed up to 2 m/s² while running at 5 m/s, it’ll count as zero. So, if we think about how fast we go when we’re running and how much power it takes, the first time is 3 W/kg and the second time is 10 W/kg. That’s more than three times as much external power, and it’s not included in the usual way of thinking about the threshold.

For anyone who’s ever wondered what ‘power’ really means in the context of biomechanics, you’re in the right place. I should know – I’ve been working and publishing in this field for 20 years, and the same goes for Prof diPrampero and his team. So, let’s dive in and take a look at this practical concept. Here, we’re going to use ‘power’ to describe acceleration-speed metrics.

The idea of a “power burst” is basically any event where someone goes close to their maximum power output, and of course, the distance they cover as well above 80% of their Pmax (see Osgnach et al. for details). When we’re looking at players’ tracking data, we think this way of explaining what was actually produced is better, because it includes both how fast they got going and how much they accelerated.

There was a paper on this by Alberto Botter at the 2025 European College of Sport Science congress in Rimini last summer (see abstract in the Figure). Looking at it in a general way, we can see that the number of ‘acceleration events’ isn’t as useful as the number of “power bursts”, and this is different for rugby and football.

One of the new things we’re going to be working on in 2026 is using satellite tracking in track and field. There’s a paper in the works about sprint events, warm-ups and how demanding they are in terms of speed, acceleration and pacing. We talked about some interesting stuff, like the speed content of the warm-up, and how many athletes don’t reach high speed (90% top speed) during training or warm-up, 400-m and 400-m hurdles pacing strategies, and flat sprints compared to hurdle sprints.

Some pilot observations with local athletes (see the Figure above) show that, compared to running the same distance without hurdles, hurdle sprinting leads to multiple high-power bursts (red stars) because you have to decelerate and then accelerate again between hurdles. So, this is something you’ve got to think about when it comes to measuring how much training an athlete does. On the other hand, a 60-metre flat sprint only has one big burst of power when you’re accelerating at the start (blue star).

At last, we’re going to take a look at basketball court efforts, and we’re putting together a lab seminar on 10 June 2026. Yannis Irid, a PhD student at the French Basketball Federation, will be presenting some pilot data at the seminar.

2025 take-home message: Yes, satellite tracking in team sport can lead to significant information about players speed, acceleration and external mechanical power output. Integrating acceleration and speed outputs into a single metric allows more detail in the analysis, especially for efforts of intermediate acceleration/speed but high power. New applications in track and field and basketball will extend this approach beyond the classical football or rugby contexts.

Workshops, training and consultancy applications

In 2025, I spent a lot of time teaching, sharing and explaining these ideas, new results and how they could be used. There were all sorts of sports and settings involved, like the French Tennis Football, Triathlon or Rugby Federations, the NCAA Football and Basketball consultancy, and lots of physiotherapists groups in France and Europe. The 2025 highlights for these teaching and training activities were probably the 10-week programme for sprint power and acceleration performance with the U17 team of our professional club in Saint-Etienne, a great and innovative 2-day workshop on “Deceleration and Acceleration Performance” with Damian Harper in Austria (check out Damian’s great papers on deceleration, such as this 2025 one), and a 2-day masterclass on hamstring injury management and sprint performance in Amsterdam with Jurdan Mendiguchia (read Jurdan’s most recent paper on a sprint table test here).

Exciting things are planned for 2026! I’m going to be teaching and consulting in the US, Mexico and Europe. I’ll be focusing on basketball and the “foot-ankle-hip-pelvis-trunk starting 5”. I’ll also be doing some fascinating research on sprint mechanics. I’ll be posting updates on social media, especially on LinkedIn and Instagram, so make sure you follow me! make sure to read my 2026 highlights blog post!